Module 4: Stress and Coping

Module Overview

We all have experience with stress. Why? Because we all have demands we are faced with daily. There is no way for us to eliminate daily hassles and stressors. All we can do is learn how to cope with these demands and the inevitable strain and stress they will cause or wait them out. The good news is that all demands eventually come to an end. Module 4 will give you an overview of stress and coping as it relates to engaging in motivated behavior. This discussion builds on goals from Module 3 and will set us up for a discussion of the economics of motivated behavior in Module 5 and behavioral change in Module 6.

Module Outline

- 4.1. Responding to Life’s Challenges – An Overview

- 4.2. Demands, Resources, and Strain

- 4.3. Problem Focused Coping

- 4.4. Stress

- 4.5. Emotion Focused Coping

Module Learning Outcomes

- Describe the stress and coping model in general.

- Clarify the relationship between demands, resources, and strain.

- Define stress and how it manifests.

- Describe ways to cope with life’s demands and stress.

4.1. Responding to Life’s Challenges – An Overview

Section Learning Objectives

- Describe the stress and coping model.

- Apply the model to your own life.

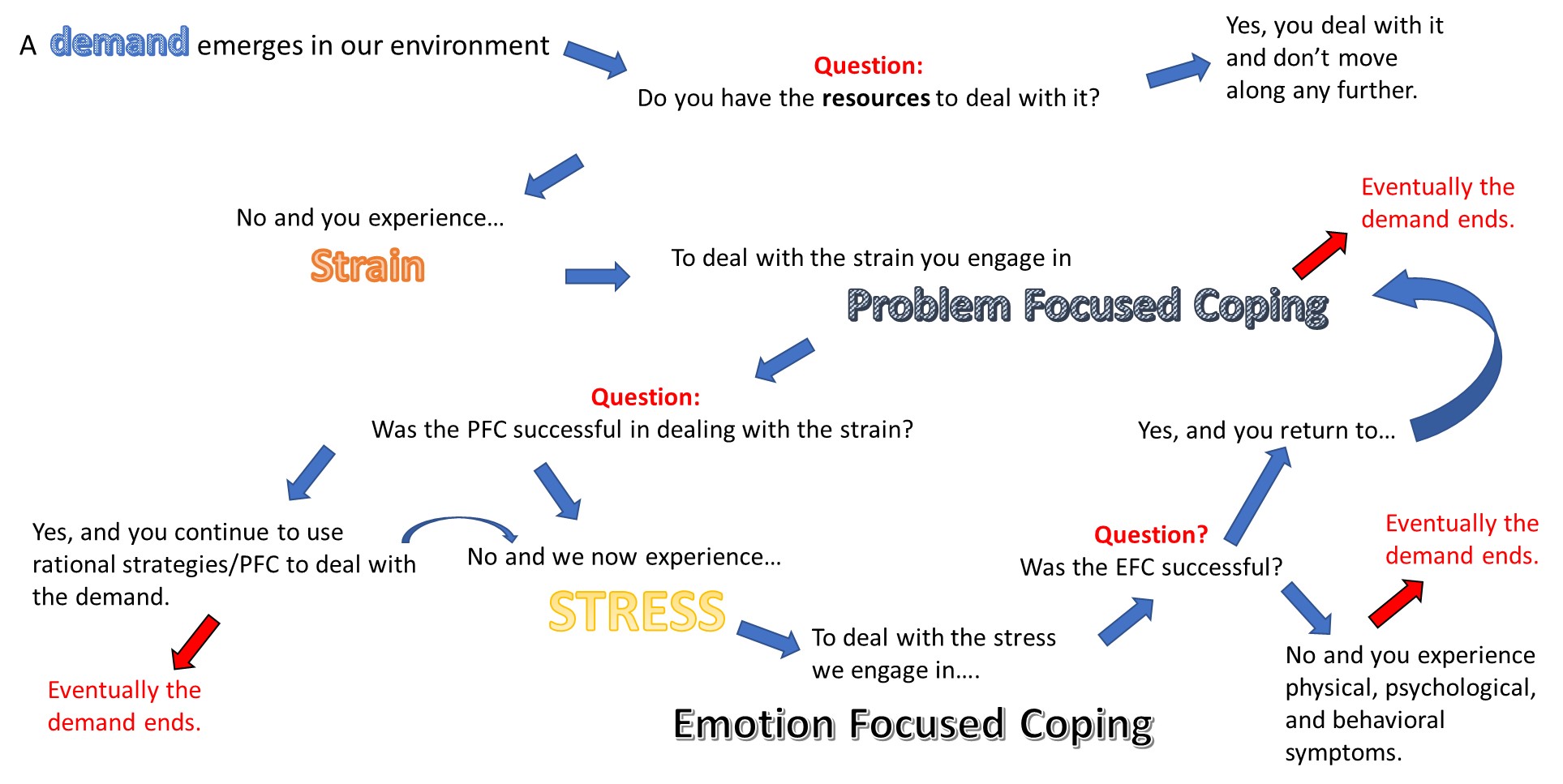

Figure 4.1: A Model for Conceptualizing Stress and Coping

The model above is a useful way to understand the process of detecting, processing, interpreting, and reacting to demands in our world. First, the individual detects a demand, or anything that has the potential to exceed a person’s resources and cause stress if a solution is not found. These demands could be something as simple as dealing with traffic while going to work, having an irritable boss, realizing you have four papers due in a week, processing the loss of a loved one or your job, or any other of a myriad of possible hassles or stressors we experience on a near daily basis. Once we have registered the demand and determined it to be emotionally relevant, we begin to think about what resources we possess to handle it. Resources are anything we use to help us manage the demand and the exact resources we use will depend on what the demand is. For instance, the loss of a job might require you to look closer at how much money you have in savings and how long that money can realistically sustain you. Or, if you have two exams and a paper due in one week, you might look at how busy your schedule is and find ways to free up time so you can get the work done. In both cases, you could use your social support network to help you out. Our resources may be fine to deal with the demand and we don’t progress any further through this process, or they may be inadequate to deal with the problem at the onset or run out if the problem persists for too long. When the latter occurs, we experience strain or the pressure the demand causes. This strain is uncomfortable and so we take steps to minimize it.

The best way to do this is to try and find a solution to the demand called problem focused coping (PFC). If we have a paper and a test in the same week you may go to your boss and ask to trade a shift with a coworker. This gives you the additional time you need to complete the paper and study for the test. If the boss refuses, you could always ask your professor for an extra day or two with the paper. These strategies might work and if so, you continue to manage the demand through rational means. If these strategies fail to manage or remove the demand, we experience stress. You might think of stress as strain magnified enormously. Whereas strain may have left us a bit anxious, depressed, or exhausted, stress takes these symptoms to a whole new level. For some demands, such as the loss of a loved one, the depression experienced in strain could reach clinical levels in stress. Now to effectively deal, you will need to consult a clinical psychologist. Or maybe when the big presentation in your Public Speaking class was a week away you only felt a bit anxious but now that it is … TODAY!!!! …and in an hour… you are feeling very anxious. Not just that, you have a sick feeling in your stomach, your hands are shaking, you are breaking into a cold sweat, etc. Now, your strain has manifested itself into something much more.

These physical, psychological, and behavioral reactions to stress have to be dealt with so you can either return to more rational strategies, if practical, or just ‘weather the storm’ and wait for the demand to pass. Hence, you employ any one of a series of emotion focused coping (EFC) strategies. Think of stress as an emotional reaction. Hold out your arms and make a circle around your head. It’s a pretty big circle. Your initial reaction may be that big. If your EFC strategy works well, your emotional reaction becomes smaller. Take those arms you likely still have in the air and start moving them in. As you do that, the circle becomes smaller. In the case of the presentation, you cannot take a ‘0’ on it so you have to confront the demand head on and do the presentation. You better start imagining your audience in their underwear! Confronting the problem is a type of PFC and so, by managing your stress successfully, you are able to return to rational approaches to dealing with the demand. Sometimes the demand is just too big and we cannot handle it. In this case, we begin to exhibit physical, psychological, and behavioral symptoms. Left unchecked and lasting for a prolonged period, these can kill us. It may also happen that we experience stress from not being able to manage the demand and then, eventually, the demand ends on its own. Excellent, and now we can prepare for the next stressor that will surely rear its ugly head sometime soon.

This is an overview of the process we generally go through. We will tackle each component in more depth in the remainder of this module. Also, be aware that in Module 5 I will add in another piece to the model.

4.2. Demands, Resources, and Strain

Section Learning Objectives

- Understand the differences between everyday hassles and stressors.

- List, describe, and give examples of the three forms of everyday hassles.

- Define stressors and explain the differences between eustress and distress.

- Compare and contrast the three types of stressors.

- Identify and describe what a resource is and give personal examples.

- Explain strain and describe how it is experienced generally (general because the nature of how strain, and later stress, are experienced will depend on what the stressor was).

4.2.1. Demands

You might think of demands as being assigned to one of two major categories – daily hassles or stressors. Within these two categories are various subtypes which we will explore.

4.2.1.1. Daily hassles. The first major class of demands is daily hassles. Daily hassles are petty annoyances that over time take a toll on us. There are three types of daily hassles.

Pressure is when we feel forced to speed up, intensify, or shift direction in our behavior. What pressures do you experience in school? on your job? in your fraternity or sorority? from your coach? We all experience pressure on a daily basis…even faculty. I have felt the pressure to be to class on time, prepare my lecture and rehearse it, complete grading in a timely fashion, and be available for office hours. I love it, though.

Frustration occurs when a person is prevented from reaching a goal because something or someone stands in the way. Examples of frustrations include money and delays. Some of you can relate to these if you have ever had to wait for your financial aid to post to your student account and did not have the money to buy textbooks before the first day of class. Then your professors are assigning readings in the first week but how do you complete them without a book? This is maybe where having a friend helps out – assuming this friend is not waiting like you are! Of course, then there are open education resources like this book that solve the problem completely.

Conflict arises when we face two or more incompatible demands, opportunities, needs, or goals. We all have experienced this one. Whether the conflict is with a roommate, significant other, boss, professor, parents, etc., these little conflicts alone are no big deal but if they keep occurring, can cause problems. Did you ever have to break up with your boyfriend or girlfriend because these conflicts became the highlight of your relationship and never seemed to resolve themselves? Did you ever drop a class or quit a job for the same reason? If so, you understand the cumulative effects of conflict.

Think about the types of daily hassles discussed above. Isolated, they are not a big deal. But have you ever noticed that what was not a big deal at the beginning of the week really starts to get under your skin by the end of the week? For instance, on Monday, having to run class-to-class, drive to work and sit in traffic, wait in line for lunch, etc. are mere inconveniences that can be dealt with. By Friday, they have become infuriating and annoying. In other words, over time daily hassles take a toll on us and we likely experience several at the same time (i.e., pressure to do well, not having enough money, and conflict with a roommate, for instance).

4.2.1.2. Stressors. The second major class of demands is stressors, a term you may have heard before. What are they? Stressors are environmental demands that create a state of tension or threat and require change or adaptation. A common misconception is that only bad things cause stress. But is this true? Can good things cause stress also? The answer is ‘yes’ and these good things are a special type of stressor called eustressors (Selye, 1976). When we think of things usually equated with stress, these are technically called distressors. Coming up with a list of distressors is easy. What are some good things that can create stress too? Might a new job be a eustressor? What about starting college? The birth of a baby? Any of these events qualify, but keep in mind that what is a eustressor to me could be a distressor to you. There are three types of stressors, whether eustress or distress:

Change is anything, whether good or bad, that requires us to adapt. What change have you had to deal with recently? If you are a first-time college student, you left home where your parents provided for you and structured at least some part of your day. You likely had rules to live by, chores to do, and siblings to deal with. Now you are on your own. You make the rules, still have chores to do but now you do them all, and instead of siblings have roommates. That is a lot of change. What about more ‘seasoned in life’ online students? Many of you have been away from the classroom environment for quite some time and so, this represents a definite change you must adjust to. Here is the simple rule with change – the more you need, the greater the stress. Or maybe I should say the greater the potential stress.

Extreme Stressors are stressors that can move a person from demand to stress very fast. Examples include divorce, catastrophes, and combat. Hopefully you haven’t had to deal with any extreme stressors recently, but if you have, they would most likely take the form of the loss of a loved one or some type of catastrophe such as a natural disaster. Why? Because we live in a country that is fortunately not experiencing war firsthand, many of you are not married and so divorce or separation is not an issue, and even if you are working, it is likely just for extra money, and so unemployment is no real threat. In your life you will encounter at least one devastating situation and the distinguishing feature of extreme stressors is their ability to move you from demand to stress very quickly. In other words, many of them create stress immediately, unless you had time to prepare. Maybe you knew your company was going to be doing layoffs and so you spent the months leading up to your dismissal putting money on the side, preparing your resume, and applying for jobs. Or maybe you knew a loved one was dying, and it was just a matter of time. So, you said your good-byes and made peace with their absence. It’s when these events occur without warning that they are most detrimental to us.

In late June 2018, friends of the family were driving home from a fun day out. They were moving along the highway and came upon construction. As law-abiding citizens, they slowed down. The problem was that behind them was a truck driver who was not paying attention to the slowing road conditions ahead and continued on, into the slowed or stopped traffic at over 60 miles an hour. Their car was the first he hit from behind and in the back seat sat their 14-year-old daughter. Emergency crews rescued our friends and their daughter and sent them all to the hospital. Our friends had minor injuries, but their daughter had serious ones and had to be pulled from her machines two days later. There was no chance of her making any type of recovery and living a full life. She was brain dead. This was obviously an unexpected turn of events and represents an extreme stressor I hope no parent ever has to go through.

Okay, so let’s face it. For many of the students in the class you have hopes of going on to graduate school after you finish your bachelor’s degree. The last four years were so fun you want to do it all again, but with the added obligations of research, serving on committees, and teaching. By setting this goal for yourself, you have created pressure to excel in the classes related to your major or have generated self-imposed stressors. In fact, one strategy you likely came up with is to focus more time on these courses and less on those that do not matter as much. This could be a great strategy but be cautious that you do not let these other classes go too much and, therefore, cause yourself the distress of failing them, being put on academic probation, and/or having to take them again! The concept of self-imposed stressors related to our topic of goals from Module 3 but will come up in Modules 6 and 7 too. Keep it in mind as we continue.

4.2.2. Resources

The next step in the process is to start figuring out something to do about the demand. The obvious task is to see what resources you have and as previously noted, these are specific to the demand. Think about what resources you would have at your disposal to handle the following:

- Daily Hassle –> Frustration –> Traffic

- Daily Hassle –> Conflict –> Constant arguing with your significant other

- Eustressor – Birth of a new baby

- Extreme Stressor – Loss of your job

- Self-imposed Stressor – Student athlete with a swim meet in one week

- Distressors – Three exams and one paper in a week

You likely made a great list of resources for each of the demands listed above. These resources may be adequate to deal with the demand and so, you have no problem. In the case of demands that arise from being a student, you are likely able to handle everything thrown at you early in the semester but as demands build on one another, your resources are exhausted and you experience strain. As you will learn in Module 5, time is one resource we all need. Writing a paper when you just have the one paper to write should not be a big deal. But what if you have two exams, a track meet, fraternity obligations, work, and….that paper to do in the same week. Time will be a precious commodity in this case.

I noted that in the next module we will expand upon our model, and it is in relation to the topic of resources. To know exactly what resources, you will need to deal with a demand, you have to know are what the costs of motivated behavior. As I noted, time is one such cost, but there are others. Hold on to this thought for now.

4.2.3. Strain

Strain is the pressure the demand causes; it occurs when our resources are insufficient to handle the demand. It may be experienced as exhaustion, anxiety, depression, discomfort, uneasiness, tension, or fatigue. This is short and sweet, but exactly what stain is. It manifests itself in different ways for all of us. Some may experience more or less of any of its symptoms and still be classified as strain.

4.3. Problem Focused Coping

Section Learning Objectives

- Define problem focused coping.

- List and describe each of the three types of PFC.

Once we determine there is a demand we need to respond to, we do just that, respond or engage in motivated behavior. If our resources have been exhausted, we experience strain and begin to use problem focused coping, which you might classify as another form of motivated behavior. Notice the name for a minute. Problem —– focused coping does just that. It is a type of coping focused on the problem itself. This problem is the demand we are facing. This should help you distinguish it from emotion focusing coping, which will be defined in a bit. There are three types of PFC:

- Confrontation – When we attack a problem head on. This might include dealing with having to learn a new skill in our job by taking the appropriate training class. Or if we are in need of money, we go to the bank to take out a loan. Recall our discussion of emotion from Module 2 and how we might respond initially. Our affective states definitely play a role here in how we view doing the training class, but also in terms of which PFC strategy we choose, if any.

- Compromise – When we attempt to find a solution that works for all parties. A great example of this is going to the movies. When we are deciding on which movie to see with our significant other, we may not always agree. Maybe I want to see the latest action-adventure movie, such as Avengers Infinity War, while my wife wants to see the latest musical, such as Mamma Mia 2. I may tell her we will see her movie this week and then next week, we can go see my movie. This represents compromise and helps avoid or end any conflict. (FYI – To my surprise, I enjoyed Mamma Mia and we have watched it again numerous times since!)

- Withdrawal – When we avoid a situation when other forms of coping are not practical. It may be a class you are taking is just too much for you to deal with. You likely have tried to find a way to stay in it and be successful, but there are just times when we need to realize our limits (see Module 1 in relation to knowledge and competence) and step away from the class. In academia, we call this withdrawing. In relationships, we withdraw from a stressful relationship by ending it. Though withdrawal may seem like giving in or accepting defeat, it is the best and most logical solution at times.

It seems fair to ask whether one strategy produces more favorable outcomes over the others. The answer is that no single strategy is better, and their effectiveness depends on the demand. For some demands, all PFC strategies may help, whereas for others, only one may be practical. In the example of having too much schoolwork in a week, we might not be able to ask a professor for an extension because we have already used that card once this semester. The same could be true of requesting time off or switching shifts at work. Hence, compromise is out leaving us with confrontation and withdrawal, but the latter is not possible either since we need the class to graduate this semester. In the case of constant conflict in our relationship, all strategies would work. We might confront the problem head on or try and find a compromise. If this fails, then ending the relationship makes sense. Again, which strategies work depends on the demand(s) we are facing.

Where do we go from here? If the strategy is successful in dealing with the demand, we proceed no further along at that time. It could be that the demand persists for a long time and our resources and PFC strategy(ies) cease being effective. In that case, we move to stress. Or maybe the strategies were not effective from the start, or if the demand is too intense in nature, then we might jump through the process right to stress, our next topic.

4.4. Stress

Section Learning Objectives

- Define stress. State what stress is not.

- List and describe methods of measuring stress.

- Compare and contrast by defining and using examples for the three physiological stages of stress (General Adaptation Syndrome).

- Define adaptation energy.

- Define and provide examples of primary vs. secondary appraisal as they relate to a single demand.

- Define psychosomatic disorders and explain how these physical symptoms of stress are caused.

- Discuss the effect of stress on the immune system.

- List psychological symptoms of stress.

- List behavioral reactions of stress.

4.4.1. Defining Stress

Stress is one of those terms that everyone uses but no one can really define. Much of what we know about stress can be attributed to the work of Hungarian endocrinologist, Hans Selye (1907-1982). Selye (1973) defined stress as “the nonspecific response of the body to any demand made upon it” (pg. 692) and pointed out that the important part of the definition was the word nonspecific. Though each demand exerts a unique influence on our body, such as sweating due to heat and so in a sense is specific, all demands require adaptation, regardless of what the problem is, making them nonspecific. Selye writes, “That is to say, in addition to their specific actions, all agents to which we are exposed produce a nonspecific increase in the need to perform certain adaptive functions and then to reestablish normalcy, which is independent of the specific activity that caused the rise in requirements” (pg. 693).

It is important to also state what stress is not since the term is used loosely. Selye says stress is not…

- simply nervous tension – Stress reactions occur in lower organisms with no nervous system and in plants.

- the result of damage – “Normal activities – a game of tennis or even a passionate kiss – can produce considerable stress without causing conspicuous damage” (pg. 693).

- something to be avoided – In fact, Selye says stress cannot be avoided as there will always be demands in our environment, even when sleeping, as in the form of digesting that night’s dinner. Furthermore, adaptation and growth can occur from it.

4.4.2. Measuring Stress

Stress is measured in a few ways. One such method is to assess daily hassles or the irritating and frustrating situations in which we feel hassled on daily basis. Consisting of 117 items, the Hassles Scale (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981) asks about crime, one’s weight (I definitely can relate to this one and my scale can attest to that), or having a myriad of tasks to do (I relate here too – what about you?).

Another method involves the examination of life events and our perception of them. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) includes 14 items that measures whether the participant viewed events in the past month as uncontrollable and unpredictable. It assesses daily hassles, major events (stressors), and changes in our coping resources.

Finally, physiological measures can be used such as the release of the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine and increases in heart rate, respiration rate, and blood pressure. Recall our earlier discussion of the sympathetic nervous system and how it responds to threatening stimuli in our environment (see Module 2). These measures are fairly reliable and quantifiable, but the use of equipment can produce artificial stress in participants, making the aforementioned scales the preferred choice of researchers.

4.4.3. The General Adaptation Syndrome

So how do we get to the point of stress? Selye (1973) talked about what he called the General Adaptation Syndrome or a series of three stages the body goes through when a demand is encountered in the world. These stages are:

- Alarm Reaction – Begins when the body recognizes that it must fight off some physical or psychological danger. The Sympathetic Nervous System activates leading us to become more alert and sensitive, our respiration and heartbeat quicken, and we release hormones.

- Resistance – This is the stage when the body is successfully controlling the stress. We move from a generalized response to one that is more localized and where the stressor impacts the body. Our body is more resistant to the original stressor but vulnerable to new stressors. Selye (1973, 1976) talked about what he called adaptation energy or your body’s ability to deal with change or demands. We all have adaptation energy, but it is finite, and you could say we have differing amounts. Maybe think of this energy and the amount of it as your threshold. If you have a lot of adaptation energy, you will have a higher threshold for stress. In other words, it will take you longer to react to stress or move into the third stage. If you have a little bit of adaptation energy, you have a low threshold. No matter how much you have, demands, whether daily hassles or stressors, use up this energy. At the start of the week, you are ready to go and your energy is at its highest. But what happens during the week? This energy is being spent dealing with one demand after another and by the end of the week, you feel exhausted. This ties in with the idea of daily hassles taking a toll across time. Add stressors to this and this energy disappears quicker.

- Exhaustion – When a person runs out of adaptation energy and the ability to combat stress, they become exhausted. Stressors can adversely affect medical conditions by intensifying, delaying recovery, interfering with treatment, or adding health risks. Psychosomatic disorders are another name given to these medical conditions and include asthma, headache, heart disease, hypertension, and ulcers. They have real symptoms with a psychological cause, or the demand we are facing. Consider your reaction to having to give an oral presentation if you are fearful of public speaking. You likely experience sweaty palms, nervousness, a queasy stomach, trembling hands, etc. What happens once the presentation is over? The symptoms go away since the demand has ended. Stressors alter the immune system, thereby increasing susceptibility to disease. Behavior changes may also affect the immune system since people under stress engage in bad health practices (i.e., alcohol use, poor diet, smoking more, and sleeping less). Psychological symptoms include depression, anxiety, reduced self-esteem, feeling worthless, anger, and frustration. Outside of the health defeating behaviors mentioned above, our behavioral reactions to stress may also include working out, watching funny movies, hanging out with friends, or seeking advice from family members.

Let’s use an analogy to understand this process. Say our country was attacked by a foreign power. Alarms would go off so that we could mobilize the military to fight off the attacker. Initially, while the military prepared to deploy, our ability to fight off the attacker would be low. Once the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines were ready to fight back and deployed to the battlefield, our ability to resist the attacker would increase. Over time, we would be responding well and adapt to the threat the attacker represents. We would be successfully resisting the attack. But if this battle took too long or another enemy force attacked us, our ability to fight back would eventually be exhausted. Why? The energy needed to fight back would be depleted and so our resistance would fall apart rapidly. This is where all the symptoms noted above begin to rear their ugly heads!

How might you relate this to your own life? Think of the last exam you had and how you moved through the three stages.

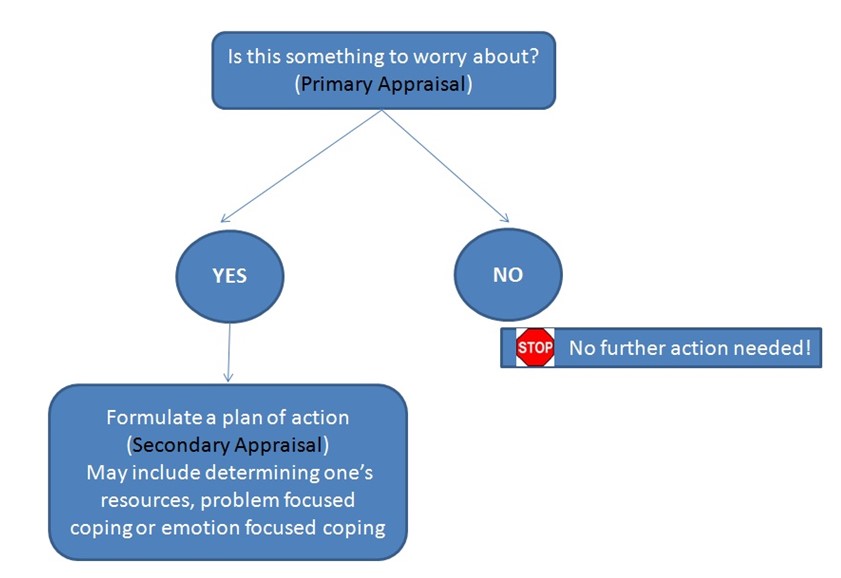

4.4.4. Appraisal

So how do we know if one of the demands discussed earlier is worth even getting worked up over? It is necessary to discuss appraisal or the process of interpreting the importance of a demand and how we might react to it (Folkman and Lazarus, 1985; Lazaraus and Folkman, 1984). When a demand is detected, we must decide if this is something we need to worry about. In other words, we need to ask ourselves is it relevant, benign, positive, or stressful? This process is called primary appraisal (PA) and is governed by the amygdala (Phelps & LeDoux, 2005; Ohman, 2002; LeDoux, 2000), which is used to determine the emotional importance of events so that we can either approach or withdraw. You might think of primary appraisal as answering the question with a one-word answer. If the question regards what the nature of the event is, we could answer with one of the words above (i.e., relevant, benign, positive, or stressful). If the question is whether this is something to worry about, then we might answer with a ‘Yes’ or ‘No.’ Either way, the answer is simple and only a word or two are required.

Let’s say we decide it is something to worry about. So, what do we do? That is where secondary appraisal (SA) comes in. You might think of it as developing strategies to meet the demands that life presents us or forming a plan of action. This is controlled by the prefrontal cortex of the cerebrum (Ochsner et al., 2002; Miyake et al., 2000). These strategies range from assessing our resources, using problem focused coping, and then later, using emotion focused coping.

A third type of appraisal is called reappraisal. Simply, this is when we change our initial appraisal due to the receipt of new information. The new information could greatly increase our stress, but it could also reduce it. Say for instance we heard that a family member was in a serious car accident. Our initial appraisal is that this is a problem (primary), and we decide to rush to the hospital to be there with them (secondary). Once there, we are told by the doctor that, though our family member is hurt, they are not in any danger of dying and should make a full recovery. Our stress reduces as a result. We might arrive and find out he/she is in surgery and is clinging to life. In this case, our stress would increase.

The level at which the brain processes information gets more sophisticated as you move from one major area of the brain to the next. The initial detecting of environmental demands occurs due to the actions of the various sensory systems and then, this information travels to the thalamus of the central core. From there, we need to determine if it is something to worry about and so it travels to the limbic system and the amygdala. Recall, too, that in the limbic system it is the hippocampus which governs memory. We also try and access memories of similar demands (or the same one) experienced in the past to know if we need to worry. Finally, we take the simple answer obtained in the amygdala, and if it is something to truly worry about, a plan of action needs to be decided upon, which involves the most sophisticated area of the brain or the cerebrum and the prefrontal cortex, specifically. So how we handle this information and what we do with it becomes increasingly detailed as we move up from the lowest area of the brain to the highest.

Figure 4.2. Appraisal Decision Matrix

4.4.5. The Effects of Stress

In our discussion of the General Adaptation Syndrome, I noted some of the effects of stress. To be complete and to emphasize their importance, as stress can kill if left unchecked, I want to reiterate them again. Stress can manifest itself as:

- Tension or vascular headaches

- Getting the cold or flu

- High blood pressure

- Cardiovascular disease

- Ulcers

- Upset stomach

- A rise in blood pressure

- Chest pain

- Fatigue

- Changes in sex drive

- Being anxious, leading to the development of anxiety disorders such as PTSD

- Irritability

- Bouts of anger

- Depression

- Losing motivation

- Inability to focus

- Withdrawing from one’s social world

- Over or undereating

- Feeling overwhelmed

- Development of diabetes

- Feeling restless

Check out the following article for more on the effects of stress:

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress-symptoms/art-20050987

I noted earlier that stress can lead to an anxiety or mood disorder. Remember, anxiety and depression are not uncommon when strain occurs, but if left unchecked, could progress to a disordered level. The DSM 5 has a class of psychological disorders called trauma- and stressor-related disorders. A stress disorder occurs when an individual has difficulty coping with, or adjusting to, a recent stressor. Stressors can be any event – either witnessed firsthand, experienced personally, or experienced by a close family member – that increases physical or psychological demands on an individual. These events are significant enough that they pose a threat, whether real or imagined, to the individual. While many people experience similar stressors throughout their lives, only a small percentage of individuals experience significant maladjustment to the event that psychological intervention is warranted. These disorders take the following forms:

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, or more commonly known as PTSD, is identified by the development of physiological, psychological, and emotional symptoms, following exposure to a traumatic event. Individuals could present with recurring experiences of the traumatic event in the form of flashbacks, distinct memories, or even distressing dreams; negative alterations in cognitions or mood and will often have difficulty remembering an important aspect of the traumatic event; be quick tempered and act out in an aggressive manner, both verbally and physically; and have difficulty with memory or concentration.

- Acute stress disorder is very similar to PTSD, except for the fact that symptoms must be present from 3 days to 1 month following exposure to one or more traumatic events.

- Adjustment disorder is the least intense of the three stress-related disorders and occurs following an identifiable stressor within the past 3 months. This stressor can be a single event (loss of job) or a series of multiple stressors (marital discord that ends in a divorce). Additionally, the stressors can be recurrent or continuous (i.e., significant illness).

4.5. Emotion Focused Coping

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify how others can buffer against the effects of stress.

- Define and explain the importance of one’s locus of control on stress.

- Distinguish between problem focused coping (PFC) and emotion focused coping (EFC).

- Identify types of EFC.

- Describe behavioral interventions for dealing with stress.

4.5.1. Help from Others

Social support is one simple way of dealing with stress. Ask others for help or advice. These others could include friends or family, your professor, a pastor, or community group. Social support lessens or even eliminates the harmful effects of stress and has been called the buffering hypothesis.

4.5.2. Locus of Control

Julian Rotter (1966) proposed the concept of locus of control, or the extent to which we believe we control the important events of our life. If we believe our fate is in our hands, Rotter said, we have an internal locus of control; those who attribute luck or fate to the events of their life were said to have an external locus of control. Where stress is concerned, believing we have personal control over our life affects how well we cope with stress.

4.5.3. Emotion Focused Coping Strategies

When PFC does not work, we experience stress. Recall earlier that stress was described as the giant circle around our heads (that is, if we held our hands up and formed a circle). The second type of coping, emotion focused coping (EFC), deals with the emotional response. This response could be intense happiness, as with eustressors, or frustration, anger, sadness, etc. To be able to deal with the demand and its stress from a rational perspective, we need to manage the emotional reaction we are having. This is where emotion … focused coping comes in. You can distinguish it from PFC if you recall that stress is our emotional reaction, and we need to manage it. There are six types of EFC:

- Wishful thinking – When a person hopes that a bad situation goes away, or a solution magically presents itself. In the case of being unemployed, we are hopeful that the next ring of the phone is someone calling to offer us a job, or our previous employer realizing a mistake was made and our services are needed again.

- Distancing – When the person chooses not to deal with a situation for some time. If we know we have a major paper due in our Psychology of Gender class, but that it is not due until the final week of the semester, we may choose in week 2 to ignore the paper until maybe week 10. This strategy can eliminate stress caused by the paper until its due date is closer.

- Emphasizing the positive – When we focus on good things related to a problem and downplay negative ones. In this case, you might say the glass is truly half full and not half empty. We call people who emphasize the positive optimists.

- Self-blame – When we blame ourselves for the demand and subsequent stress we are experiencing. A student failing a class may attribute his/her lack of success to being stupid or ill-prepared for college.

- Tension reduction – When a person engages in behaviors to reduce the stress caused by a demand. This strategy may include the aforementioned behaviors of using drugs or alcohol, eating comfort foods, or watching a funny movie.

- Self-isolation – When a person intentionally removes himself from social situations to avoid having to face a demand. A student who is struggling in a class may choose not to go to the class anymore. If the problem goes beyond just this one class, he or she may completely stop going to class and stay in his/her room.

Bear in mind, that at times, we may not be able to use any rational strategy to deal with a demand (PFC) and can only wait until it passes or ends. To be able to do this successfully, we need to manage the emotional reaction (EFC) while the demand is present.

4.5.4. Behavioral Interventions

And finally, outside of the techniques mentioned above, a few other strategies could be used to include:

- Stress Inoculation (Meichenbaum & Cameron, 1983) is a form of Cognitive Behavior Therapy in which a therapist works with an individual to identify problems (the conceptualization stage), learn and practice new coping strategies (the skills acquisition and rehearsal stage), and finally put these newly acquired skills to use (the application and follow through stage).

- Emotional disclosure occurs when a therapist has a client talk or write about negative events that lead to the expression of strong emotions.

- Mindfulness asks the individual to redirect their past- and future- directed thoughts to the present and the problem at hand.

- Relaxation Training focuses on the use of deep muscle relaxation exercises.

Module Recap

Review the model presented at the beginning of the module one last time. Think about how your experience with the world makes you better suited to deal with some types of stressors encountered again later. For instance, a study by Toray and Cooley (1998) compared first year and upper-class female students, in terms of what coping strategies they used during finals week. Baseline measures showed that neither group differed in their level of stress at that time or in their perceived test-taking abilities. But as the study showed, they differed in what coping strategies were utilized. The experimenters found that first year students used the EFC strategies of distancing and self-isolation, whereas upper-class students used PFC and self-blame to manage the stress created by finals. This suggests that over their academic career, students learn which coping mechanisms best help them deal with the demands of college life. Reflect on this in terms of your own life.

2nd edition